2016 is teeing up to be an interesting year for discussion about education and exam standards.

Ofqual launched a

consultation about the relative difficulty of different subjects – seeking to address the essentially unanswerable question of whether my French A Level is worth as much as your Physics A Level – and a

report on the marking of music assessments from researchers at Birmingham City University criticised inconsistent and unreliable marking of music examinations.

This focused particularly on the composition element of A Level Music and found that many of the music teachers interviewed (albeit based on a rather small sample size of 71) said they felt assessment requirements were unclear. There is an irony about this because in all the many discussions over the years about standards no-one has ever claimed (as far as I’m aware) that exams for proficiency in individual musical instruments (Grade 1-8) have been subject to grade inflation.

Of course what this suggests is that there is a widely shared appreciation and internalisation of competence levels in instrumental musicianship among the professional community that teaches young people to play musical instruments, and that that professional community is trusted by those being assessed. What the research on Music A Level has highlighted, in contrast, is that there is (unsurprisingly) much less unanimity about what constitutes excellence in musical composition. This reflects the reality that standardised marking of essay and other judgement based subjects, such as History and English, can mean that candidates with offbeat but interesting answers may sometimes end up losing out – and this would perhaps apply by extension even more strongly in a subject like music.

The New Year also saw an announcement by Nicky Morgan that 11 year old pupils in the maintained sector will from next year be tested on their mastery of multiplication tables. Jo Boaler, Professor of Maths Education at Stanford University, criticised the move on the grounds that requiring children to learn multiplication tables causes “crippling fear” and “puts them off maths”, criticism echoed by John Dunford, former Secretary General of the ASCL and himself an ex maths teacher. Of course, this doesn’t seem to be a problem in China or Singapore, where it is taken for granted that pupils should be required to learn their times tables, and the truth is that it is one of those totemic issues that tends to polarise professional opinion, rather like whether or not calculators should be permitted in exams. On that question, our own records suggest there were five shifts backwards and forwards on this between 1990-2012, demonstrating just how contentious such issues can be. There is also a cultural dimension, and it is hard not to suspect that some of the same drivers - mainly anxiety about public exposure of failure - that saw the end of the learning and classroom recital of poetry are at work here as well.

Memorisation is, of course, an essential element in the learning of modern languages, and George Eustice MP is now campaigning to have Cornish re-instated as a GCSE. Given that GCSE and A level provision in lesser taught but much more widely-used and spoken languages like Turkish and Polish is under threat for, amongst other things, financial reasons (our own estimates suggest a cost of around £2m to re-develop the three lesser taught languages OCR is responsible for and annual running costs in the region of £800K) there is no chance that Cornish will be re-introduced. It is interesting to reflect that qualifications were available in Cornish – and other community languages – until quite recently through the Asset Languages programme. However, these were eventually withdrawn because of lack of demand, a function both of the scarcity of qualified teachers and lack of any special recognition in school performance monitoring.

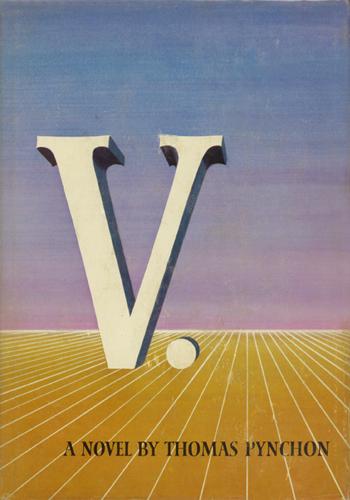

The challenges of using school education to support the survival of minority languages with few or no native speakers all brings to mind the sad plight of the lady pathologist from the Isle of Man in Thomas Pynchon’s novel “V”, who had the distinction of being the only Manx monoglot in the world…and hence spoke to no-one.

Simon Lebus

Group Chief Executive, Cambridge Assessment