Candidates finished sitting their A Levels and GCSEs last week. Compared to previous years, it was a relatively quiet session, with fewer stories than usual about difficult papers, impossible questions and administrative foul-ups. One consequence of the widespread use of social media is that candidates' exam postmortems, previously the subject of private exchanges as they left the exam hall, are now immediately published on various social platforms with audiences in their 1000s. Examples this year have included both complaints about specific questions (the inclusion of a question about bees in an A Level maths exam last month prompted notable levels of Twitter activity, though not quite as much furore as Hannah’s sweets, which made national news last year) and complaints that some papers had not covered those parts of the syllabus that aggrieved candidates had hoped (and revised) for.

Another relatively new phenomenon is the instant appearance of online petitions calling for grade boundaries to be moved downwards (though no evidence so far of the reverse effect - requests for boundaries to be raised on 'easy' exams). This particular phenomenon "Candidates' exam postmortems are now immediately published on various social platforms with audiences in their 1000s."

illustrates the way students have changed how they engage with education. It is only relatively recently that students sitting their GCSEs have even been aware of the concept of grade boundaries, let alone felt that they could legitimately ask for changes to them. That awareness is encouraged by the common contemporary practice of students being taught the syllabus with the mark scheme of past exam papers by their side. At one level this helps equip them to do the best possible job of showing what they know; at another level (it could be argued) it also equips them to 'game' the system.

Behind this lies a tacit concept of what constitutes fairness in an exam; part of that concept involves an assumption of some degree of predictability and part of it an erroneous assumption (given that exams are always, in their nature, a sampling exercise) that the syllabus as taught is comprehensively rather than selectively examined.

Exam board spokespeople tirelessly provide quotes in response to these news stories, but it inevitably proves near-impossible to explain the complex process of how exam papers are designed in one easily-swallowed sound-bite. In order to try to demystify this we "Behind this lies a tacit concept of what constitutes fairness in an exam."

have made a short video that explains how an exam paper is made. Hopefully it will be more reassuring than the comment made earlier in the summer by an exasperated exam board spokesperson in response to complaints about a difficult Chemistry A Level paper that "Exams aren't meant to be easy and students are obviously going to talk about that on social media, but everything in the paper was on the syllabus… If it looks like students did find this exam especially difficult, the grade boundaries will reflect that – so no need for petitions."

Difficult questions are not the only hazard faced by candidates. Traffic caused by revellers on their way to this year’s Glastonbury festival left some A Level students from a nearby school unable to get to their exam on time, and a GCSE chemistry exam was interrupted by several fire alarms at a Bristol school. There are procedures in place to protect students in these situations which are clearly set out in JCQ guidelines. One of the guiding principles is that students should be kept under exam conditions during any "Students during the Second World War would get taken down into air raid shelters mid-exam, with the exam often continuing in the shelter."

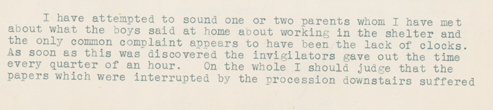

disturbance, and in particular that they are not able to access the internet or talk to each other about the question paper. An intriguing pre-internet example comes from our archives and relates how students during the Second World War would get taken down into air raid shelters mid-exam, with the exam often continuing in the shelter. Students taking their exams in these conditions had to contend with a lack of clocks and the image below shows how invigilators tackled this by calling out the time every 15 minutes to keep students on track. (You can read the letter from our archives in full, split into two PDFs at the bottom of this page)

With the end of the exam session in schools, the next phase is making sure all the marking is completed in time for results; for those interested, we have produced another short video which explains what happens to each paper between when the exam is finished and results day.

Simon Lebus

Group Chief Executive, Cambridge Assessment

Related materials