It goes without saying that the Covid-19 pandemic has had an unprecedented effect on education worldwide. In the UK alone, it led to nationwide school closures in March 2020, with most children receiving remote education until the start of the new school year in September 2020. Increases in Covid-19 cases led to a second period of school closure in January 2021, with students again learning remotely until March/April 2021. Remote education can take various forms, but in many contexts, it has relied on the use of digital technology.

When we talk about digital remote education we generally mean education that is happening outside the physical classroom, where the teacher is not present in the same physical location as the pupils, and which is delivered through digital technologies. This includes any blended learning that relies on digital technology.

There are concerns that the move to remote education has led to inequalities in access to learning. Specifically, there are concerns that there is a digital divide, resulting in digital inequality, with already disadvantaged children being most affected.

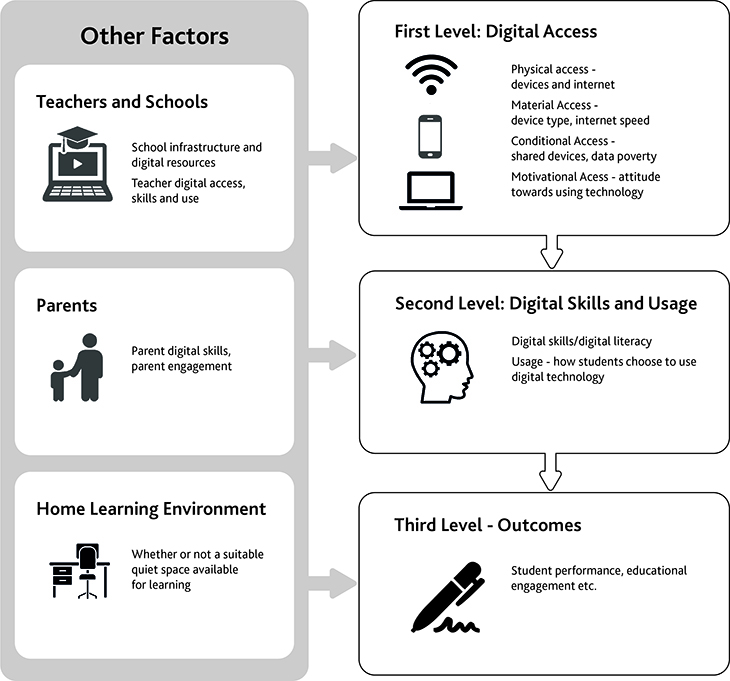

The digital divide has various dimensions: as well as access to devices and internet, digital skills are important, as are external factors such as parental support, teacher skills and learning environment.

Here at Cambridge Assessment and Cambridge University Press we have developed a set of outline principles that we believe will help all those that are interested to continue the debate around teaching, learning and assessment. Two of those Principles feel particularly relevant here:

Excellence in teaching and elevated attainment can be supported by well-designed and carefully-chosen technology that can support teaching and attainment.

and

Access to high quality teaching and learning materials is essential for high quality, manageable education at all ages.

We reviewed research into education during Covid-19 related school closure in the UK, looking at evidence relating to the digital divide. You can read the full report on our website here, but here are some of the key points we found.

Firstly, these reports provide evidence of a digital divide in terms of access to devices. While inadequate access to devices was less of a concern in private schools, most state schools reported challenges for some pupils, particularly in the most deprived schools. The increased use of digital remote education practices in January 2021, particularly live methods such as videoconferencing, may have led to increased digital exclusion due to an increased requirement for device access and quality internet.

Internet access was examined by fewer of the studies; while most students seemed to have access there was evidence of poor-quality internet, or lack of adequate data for some students. Overall, it appears that there remained a digital divide in terms of access in January 2021, despite efforts to supply devices and increase internet provision. If digital education practices become more widespread in the future as some predict (Cambridge Partnership for Education, 2021) schools and government will need to ensure that all students have access to adequate devices and internet so as to mitigate digital exclusion.

Very few of these studies examined digital skills and so there is limited evidence around this dimension of the digital divide. Young people are often assumed to be digital natives and to have strong digital skills, but this is not necessarily the case (ECDL, 2018). Digital divide factors interact with one another: those children who are digitally excluded in terms of access to devices are more likely to have more limited digital skills and so their digital exclusion may be compounded. Consequently, the issue of adequate digital skills needs to be examined in future work, especially if we move towards greater use of digital education practices.

There was evidence of the impact of other factors, such as parent engagement and both teacher and parent skills. Should digital education practices become more commonplace, efforts will be needed to ensure both teachers and parents gain adequate digital skills, and parental engagement may remain a challenge in some circumstances. Unfortunately, home learning environment is not something easily addressed, and so we need to stay aware of the different home learning environments that learners are in and the impact that this has on their ability to engage in remote digital education.

Given the recency and ongoing nature of the Covid-19 pandemic, there is still fairly limited published research examining aspects of the digital divide in education. Most research has focused on the first period of school related closures and the digital divide has generally not been the focus of research, but aspects relating to it such as device access, have been included.

Covid-19 may continue to impact education for some time, and digital education practices are predicted to become more widespread. Consequently, even though most students in the UK have now returned to in-person schooling, the digital divide will remain a challenge for education and must be examined and addressed to ensure that disadvantaged students do not fall further behind.