What is the future of English language teaching in schools? What do we need to do to support the future of English language education? Who decides on the curriculum? These were the questions discussed on the final day of our SHAPE Education: The Future of Schools event. Read a summary of the discussions in this final part in our series of blogs reflecting on the week-long event.

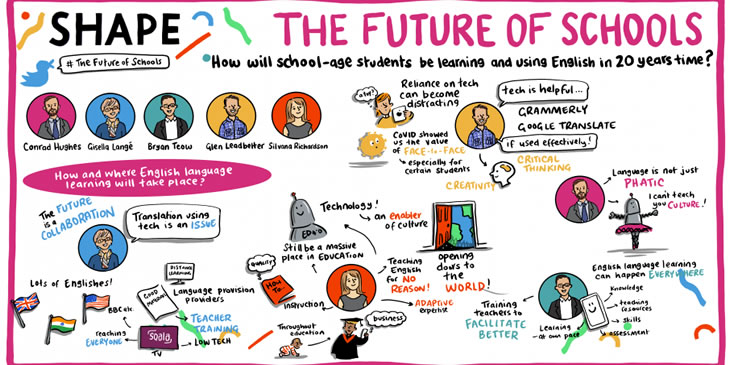

On the last day of SHAPE Education: The Future of Schools, we held a fireside chat to reflect on the discussions throughout the week and bring together different panel members to talk about the future of schools. For the final session, we were joined by Glen Leadbetter, Conrad Hughes, Silvana Richardson, Gisella Langé, and Bryan Teow and, together, we discussed questions including:

- What is the future of English language teaching in schools?

- What do we need to do to support the future of English language education?

- Who decides on the curriculum?

Read on if you’d like to see what was said in relation to these questions and be sure to watch the videos for Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of the fireside chat.

The future of English language teaching

To open the discussion, Silvana shared her views on the future role that English will play in formal education. She noted that the likes of CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) and EMI (English as a Medium of Instruction) are key ways in which education will evolve as English increasingly becomes a language that other subjects are taught through and not just a subject in itself – a prediction also made by Mike Solly on day two. Silvana also thought that learners will want specialised English instruction e.g. business English. But, she also predicted a growth in informal learning through technology for example – a topic discussed in detail on day four.

Interestingly, the question of technology evoked a debate around whether or not there will be any need to learn languages with translation technologies ever improving. Conrad, Glen and Gisella, took the view that learning a language is also about learning a culture and they questioned the capacity for technology to teach culture, with Gisella stating that “to learn a language means to get into the minds and attitudes of people speaking that language. The intercultural issue, in my opinion, will never be solved by the machines.” That being said, Bryan and Silvana also pointed out that technology could be used to teach language and even enable cultural awareness. So, in 20 years’ time, do you think we will be teaching language?

Developing approaches to English language education in schools

To support the future of education, the overwhelming response from the panel was to focus on teacher training. Gisella reflected on the past year, saying that teachers in the online pivot were not always fully equipped to make the transition. She also cautioned the digital movement, reminding us that not everyone can access technology – a recurring topic at the heart of SHAPE, also discussed by Teocah Dove on day one. Bryan, like Gisella, also noticed this challenge but saw the pandemic as a space for disruptive innovation, where technology could address future needs in teacher training, such as those discussed by Silvana and Glen. Silvana also noted that as we move to change our teacher training practices, we could start to think more about teachers’ motivations and individual aims to empower them – a notion we saw earlier in the week in Heather McGowan’s talk on day three.

Who decides on the curriculum?

Another interesting part of the fireside chat centred around the notion of learner-driven curricula. When polled on “who will be deciding the English ‘syllabus’ for each learner in 2040?”, the majority of attendees opted for the learner. For Conrad, though a pleasant notion, it raised questions about the role of syllabi in education and the roles of teachers and experts in guiding learners’ choices. The discussion that followed considered the importance of knowledge as well as skills and critical thinking with Conrad urging us to remember how important it is to build knowledge, not just skills, stating that “not only is it important to know a lot, in the 21st century, you need to know more”. The conversation picked up on ideas such as competence-based syllabi and non-disciplinary teaching that were also discussed on day two of the event.

Closing thoughts

In closing the fireside chat and the SHAPE Education: The Future of Schools event, the panellists highlighted the importance of identity, the self, and motivation for guiding the future of education. Gisella argued for the need for localising English language learning in learners’ own contexts. Likewise, Silvana called for more classroom work on translanguaging and Bryan and Conrad shared their experiences of engaging and developing multilingual learners. Finally, Glen closed the chat, refocusing our attention on the importance of developing effective teacher training, equity of representation, and using near-peer role models to support language learning.

Over the course of this event, the aim of the talks and conversations was to identify the challenges and uncertainties we face in planning for the future of education and schools. Taking a different perspective each day, we hoped to try to better understand what we can do and what we can avoid while we, as educationalists, move to address the emerging challenges in our practice. You can recap on all the talks and do keep any eye out for our report on the event.

SHAPE Education is an initiative supported by Cambridge University Press & Assessment and Cambridge Judge Business School.