We have all sat exams and are familiar with the idea of having papers marked. In many cases these marks are then converted into grades, but why? This is the question we tackle in this first of four blogs in a mini-series focused on grading and standards.

What is the difference between marking and grading?

Marking involves deciding how well students answered the questions on a test or exam and how many marks their answers should be worth. For GCSEs and A Levels here in England, trained markers make these decisions having undertaken bespoke training each year – known as standardisation – and the quality of their marking is overseen by senior examiners.

Often markers look for points that have been made – particular words or phrases, or stages of a calculation – and award marks to these. In longer questions, markers may use a levels-based mark scheme that describes the quality of answer that is needed to obtain a particular mark. The total mark for the paper is found by adding up the marks for all the questions.

Grading is the process of turning a numerical mark into some form of grade, usually a letter like the A*-E grades for A Levels, or a number like the 9-1 grades for GCSEs. The minimum number of marks needed to obtain a particular grade is called a grade boundary. These grade boundaries are usually set for each exam series, for both individual papers and the overall qualification, in order to take into account differences in the level of difficulty of the exams. This is done using statistical information supported by judgements made by senior markers.

When are grades useful?

Many tests don’t need grades. In schools, for example, teachers might find students’ answers in class tests or their mark sufficient information to inform their needs, rather than taking the additional step of constructing grade boundaries.

Grades are useful, however, when there is a need to compare results across many different tests. If everyone sat identical papers, marks may be sufficient, just as in class tests. But this is not possible in many circumstances. For example, when selecting people for job applications or university entrance, they will often have sat different exam papers, potentially from different exam boards, in different years that will all vary slightly in their difficulty, and even potentially in the number of total marks available.

In these cases, grades can provide a solution.

Do other countries use grades?

Many exams and assessment systems around the world use grades when they report their results. The International Baccalaureate, Advanced Placement (USA), French Baccalaureate and Abitur (Germany) are all examples of exams that report their results on some form of grading scale.

What are the challenges with using grades?

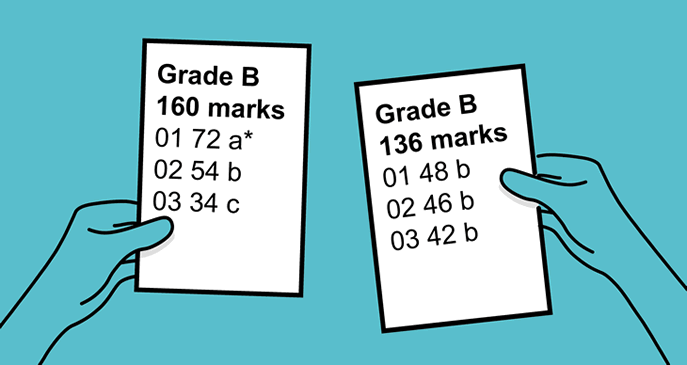

Grades can provide an easy yardstick for users of qualifications, but they can also mask differences in marks between individual candidates – which can either be large or small. For example, two students with the same grade could have a completely different profile of marks on individual papers, or a large difference in their total marks. These differences could be important to some users of the qualifications. It’s also important to remember that whatever marks are awarded, some students will always sit immediately either side of every grade boundary. So while there may be large differences in the marks awarded between some candidates within a grade, the difference between any two candidates between grades can always be just one mark. That emphasises the importance of having some means of verifying the quality of work at each grade boundary.

These are just a couple of simple examples of challenges with using grades, of which there are others. These challenges underline the need for those designing qualifications to consider both the best means of assessment and the mode of awarding in combination, so that those using the outcomes can have confidence in what the results mean.

Are there alternatives to grades and marks?

Some assessments and exams, such as the PISA(1) and TIMSS(2) tests, the Gaokao(3) exam (China), the key stage 2 national tests(4) and many Cambridge English qualifications(5) report their results on a numerical scale . Students’ marks are adjusted to ensure that they have the same meaning for different versions of the test.

There are many different methods of adjusting the marks. Some tests, such as PISA and TIMSS, include some questions from previous versions of the tests and use performance on those questions as the basis for the adjustment. Others, such as the national tests, pre-test their questions and use students’ performance on the pre-test to adjust the marks. It is also possible to use the distribution of students’ marks along the mark range, and adjust the marks so that the distribution remains as similar as possible on the adjusted scale for different versions of the tests.

Can these alternatives be used for GCSEs and A Levels?

Adjusting the marks onto a numerical scale would be difficult. It would not be possible to reuse items for GCSEs and A Levels while the past papers are released for teachers and students to use. Students would already be familiar with the questions and many students would receive full marks for them.

GCSE and A Level questions are not currently pre-tested. If they were, it would be difficult to keep the questions secure, preventing them from being shown or discussed on the internet. It would also be expensive and time-consuming to pre-test the number of exam papers that are produced and it may be difficult to recruit enough schools.

No system is without potential downsides, and even where numerical scales are used, it is often still necessary to group the scaled marks for some purposes to make them useable. For example, in China the Gaokao marks are placed into three tiers for university entrance . The need to put the scaled marks into groups means that there are similar challenges to grade boundaries; Chinese students with a scaled mark below the cut-off for the tier are not admitted to universities in that tier, even if they are only one point below.

Future blogs

In this blog I have discussed several different ways of reporting students’ results. Each of them has particular benefits and drawbacks, making them differentially suited for different contexts and purposes. In the next three blogs we discuss standards, how the pandemic has affected grades and standards.

This blog forms the latest in our series on blogs on our outline principles for the future of education through which are dissecting the importance of textbooks and other learning materials, the curriculum and assessment, as well as approaches to learning and schools themselves.

References

1↩ PISA: OECD (2019), How PISA results are reported: What is a PISA score?, in PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, OECD Publishing

2↩ TIMSS: Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., Kelly, D. L., & Fishbein, B. (2020) TIMSS 2019 International Results in Mathematics and Science. Boston College, TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center

3↩ Gaokao: UCAS (2018, December 6) China: Gaokao

4↩ Key stage 2 national tests: Standards and Testing Agency (2019, July 9) Understanding scaled scores at key stage 2.

5↩ Cambridge English: Cambridge Assessment English (2019) The Cambridge English Scale explained. UCLES.