Understanding grading, standards and grade inflation in England

Do you really know what A Level grades in England mean and how they are determined? And do you understand what is meant by grade inflation? In this blog, we invite you to explore these concepts with us as we attempt to minimise the mystery and provide clarity.

Let’s begin with standards…

In the context of A Levels in England, standards refer to the quality of performance required by students to achieve certain grades(1). The standard setting process begins with defining the curriculum(2), which forms the basis for setting examinations.

How are standards maintained?

After students have taken exams and they have been marked, the awarding bodies (under the oversight of Ofqual(3)), analyse student performances to ensure that standards are maintained(4). They make sure it is no easier or more difficult to get a certain grade in one year than another, or with one awarding body than another(5). If there are compelling concerns that standards differ across subjects to the extent that this causes students to avoid certain ‘difficult’ subjects, Ofqual will also take action to address this(6).

A combination of expert judgement and statistical evidence

Experts, such as awarding body staff and experienced examiners, play a vital role in maintaining standards. They work together in teams to maintain standards by setting the grade boundaries for each exam every year. These are the minimum raw marks students need for each grade. Exam board staff use statistical information, supported by examiner judgement, as a guide to determine the boundaries(7), and there is ongoing research to help make their judgments as reliable as possible(8).

The statistical information consists of data about the prior attainment of the students (e.g., what they achieved at GCSE). This provides guidance about the ability of the students as a whole compared to previous years. The experts also consider feedback from senior examiners, data on how students performed on each question, and statistics about the reliability of the exams, amongst others.

The experienced examiners analyse how students performed in one year compared to previous reference years by comparing the exam papers and students’ responses. They come to a collective decision about what quality of performance this year is equivalent to the standards, also considering the relative difficulties of the exam papers(9). Although the papers are designed to have the same difficulty each year (to maintain standards), it is not possible to predict this precisely(10). The raw marks required to get each grade can be adjusted accordingly to compensate for this.

Grades carry the standard

Because of how grade boundaries are set each year, the grade carries the standard, not the raw marks. A lower pass mark one year probably just indicates that the exam was more difficult than in previous years.

Is grade inflation a problem in England?

When people talk about grade inflation being a problem, the concern is usually about more students getting higher grades than in the past. People worry about standards falling when it’s perceived that what is needed to obtain certain grades declines with time, making it easier to achieve higher grades. There is a view that standards falling will mean our students are unprepared for their next steps, or our education system is less globally competitive. However, as explained, this is currently controlled for by the standard maintaining process and grade inflation generally does not occur in normal times. There are, however, some instances in which more students getting higher grades might occur, and where it may be justified, for example:

- When expert judgement is prioritised over statistical information(11). An extreme example of this was the centre assessed grades in 2020 due to Covid-19 disruption.

- If a year’s group of students genuinely demonstrated performances worthy of higher attainment.

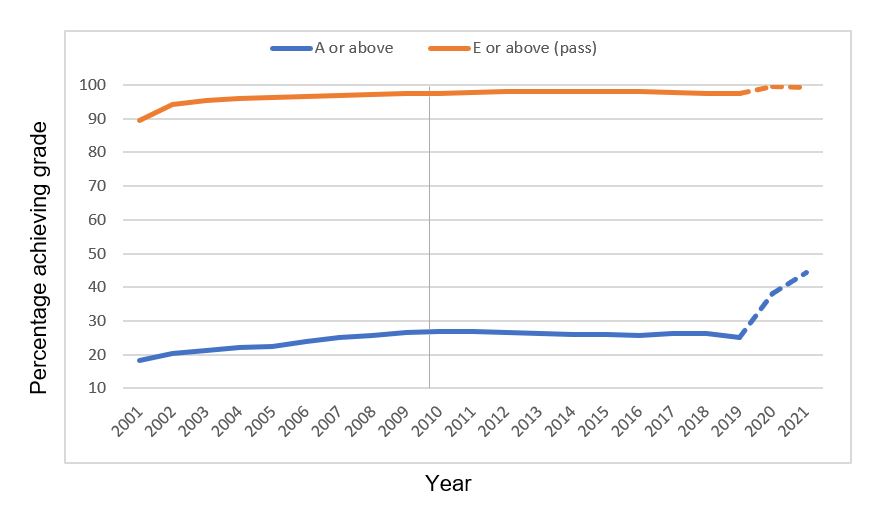

There may also have been slight grade inflation in the past, but since the measures described earlier in this blog to maintain standards were introduced in 2010, grade inflation has not been a concern in normal times. As the graph below shows, the pass rates and A grade rates across all subjects in England have been stable for the past decade since these measures were taken (indicated by the vertical line), with the exception of 2020 and 2021 (indicated by the dashed lines)(12). Since 2010, and in normal times, the experts ensure that the quality of performance needed to attain each grade each year remains equivalent.

What about the impact of Covid-19?

Hopefully, this blog has helped you understand how grading and standards work for A Levels in England in normal times. As Newton(13) explains, the standards are neither norm nor criterion referenced(14) - they are attainment-referenced. The grades carry the standard, and the process of adjusting the grade boundaries ensures that grades mean the same in different years regardless of their difficulty and which awarding body offered them. The system works, in normal times, to prevent unwarranted grade inflation.

Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has created a challenge for the standards for the 2020 and 2021 grades and for the future – we will address this topic in our forthcoming blogs. And if you would like to know more about marking, read our previous blog on, ‘Why do we convert marks into grades?’.

This blog is the latest in our series of blogs based on our outline principles for the future of education through which we are dissecting the importance of textbooks and other learning materials, the curriculum and assessment, as well as approaches to learning and schools themselves.

References

1↩ What is the Sawtooth Effect?

2↩ Alternative conceptions of comparability

3↩ The Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual) regulates qualifications, examinations and assessments in England.

4↩ A simple guide: Assuring OCR’s Marking Accuracy

5↩ Maintaining standards in summer 2019

6↩ Inter-subject Comparability

7↩ An excellent article by Newton explains how the relative emphasis on expert judgement versus statistical information has waxed and waned over time. Demythologising A Level Exam Standards, Maintaining standards in summer 2019, OCR, guidance on examining, part 4 – your results

8↩ For example, using comparative judgement. Improving awarding: 2018/2019 pilots

9↩ Maintaining standards in summer 2019

10↩ Without using pre-testing, which is not feasible in high-stakes test settings

11↩ Newton, P. E. (2021). Demythologising A Level Exam Standards, Research Papers in Education, 1-32

12↩ Data for this graph was obtained from the Joint Council for Qualifications: examinations results. The data is for all A Level subjects for the summer session in England. The approaches to determining grades in 2020 and 2021 were different from previous years, due to Covid-19 disruption.

13↩ Demythologising A Level Exam Standards

14↩ Norm-referencing, as the term is understood in England, is when each grade is awarded to the same percentage of students year after year. Criterion referencing is when each grade is awarded to everyone who meets a certain set of predetermined criteria for that grade. Demythologising A Level Exam Standards